Sentient Clit: the Pussification of BioTech

Jiabao Li, WhiteFeather Hunter, 2024

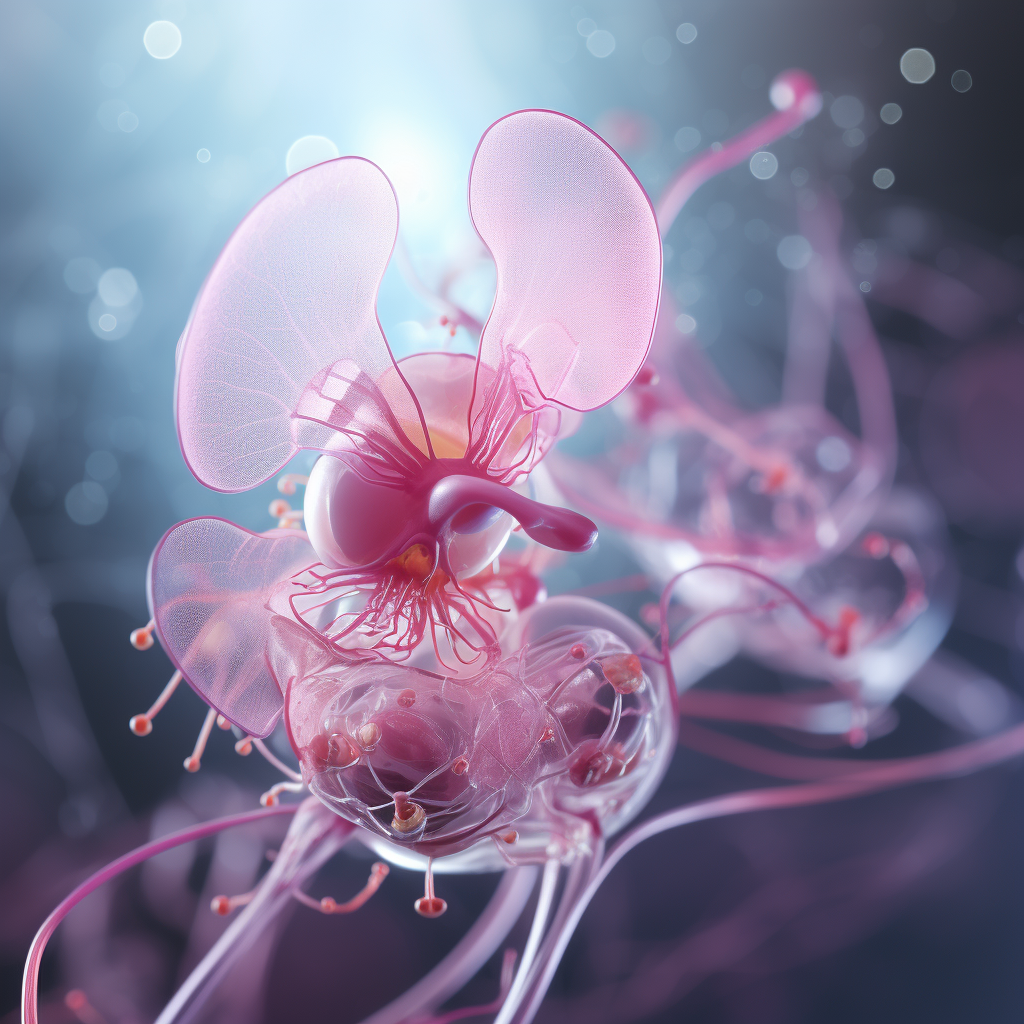

We investigate the potential of lab-grown clitorises created by 3D bioprinting stem cells derived from menstrual fluid. Our approach challenges male-dominated narratives in tech spaces, advocating for a feminist, nonbinary methodology focused on pleasure and eroticism beyond reproductive function. The project is conveyed through video performances, scientific experiments, and digital art, fostering a multifaceted discourse on posthuman pleasure, ethics of sexuality, and the deconstruction of gender norms. We scrutinise the ethical complexities of bioprinted organs capable of neural responses, questioning notions of consent and sentience in bioengineering. The use of social platforms like OnlyFans for disseminating our work strategically disrupts traditional digital consumption patterns. Through this, we address biocapitalism and control of narratives around sex and pleasure, questioning normative uses of technology in spaces that objectify bodies. Our project calls for a reevaluation of biotechnological advance in its cultural, ethical, and societal impacts, challenging existing paradigms and fostering inclusive scientific exploration.

感知之花:生物科技的柔性变革

我们探究了利用经血中的干细胞,通过3D生物打印技术在实验室中培育出 Sentient Clit 的可能性。我们的研究挑战了科技领域内的男性主导叙事,提倡一种超越生殖功能,专注于快感与情感世界的女性主义和非二元性别的新思潮。本项目通过视频表演、科学实验和数字艺术呈现,激发了关于后人类愉悦、性伦理和性别规范解构的多维对话。我们深入探讨了能产生神经响应的生物打印器官的伦理复杂性,质疑生物工程中关于意识与同意的概念。我们所选择的传播成果的平台策略性地颠覆了传统的数字消费模式。通过这种方式,我们对生物资本主义提出质疑,探讨技术在物化身体空间中的传统应用。我们的项目呼吁重新评估生物技术进步在文化、伦理和社会影响方面的作用,挑战现有范式,促进包容性的科学探索。

Exploratorium: Sexplorations

WhiteFeather Hunter’s website

Direct tissue explant/ primary cell culture from cup to dish (menstrual cup to petri dish), cultured in n2b27 + (murine) fgf + (murine) egf for 44hrs, time lapse microscopy at 40x magnification. Displays initial stages of stem cell differentiation on the neuronal pathway, with formation of dendritic protrusions. Produced at the Institute for Molecular Medicine, uLisboa. © WhiteFeather Hunter, 2024

3D bioprinted clitorises seeded with cardiomyocytes © WhiteFeather Hunter, 2023.

Video still, 3D bioprinted clitoris form in support gel © WhiteFeather Hunter, 2023.

When’s the last time you had an orgasm? Was it technologically mediated, involving a prosthetic or device? What if you were able to grow your own fleshy ‘toy’ and your personal connection to it was not just creative but also biological? How would that feel, what would it mean, and what would it look like? The collaborative project we present in this paper, Synthetic Sentience: The Pussification of Biotech is an exploration of how biotechnology could be used to facilitate sexual autonomy and pleasure through 3D bioprinting clitorises; these synthetic organs are cultured in vitro, embedded with neuronal and heart muscle cells differentiated from our own menstrual stem cells. We are compelled to create these clitorises, using our menstrual fluid as a resource, to engage with technological tools on our own terms and with our own biomaterials.

The tech spaces we have worked within were typically saturated with (solutionist) tech-tosterone objectives and approaches that did not always align with our open, exploratory feminist playfulness. Additionally, as feminist technology studies researchers have noted, “vastly more women are “on the receiving end” of technologies than create them,” particularly technologies concerned with our reproductive organs. We are interested in how our creativity can be used to style a femme or nonbinary philosophy and methodology that gives us more agency with our experiments and takes into account our various embodied experiences – not just those concerned with biological reproductive functioning but also with pleasure and erotic play.

We examine possibilities for the above through collaborative creation of technologically mediated artworks, around the idea and production of our in vitro clitorises. These works are presented in multiple formats: video/online performance and live engagement, prototyping, digital rendering, and bioengineering. Our modes of presentation are used to facilitate a generative stream of related works throughout the project development.

Some of the conceptual topics we explore include posthuman possibilities for pleasure in synthetically sentient organs and notions of the disembodied self, as well as social considerations such as the biopolitics of pleasure and ethics of sexuality. We also address the ways in which our modes of presentation may challenge normative uses of tech and tech-mediated spaces where they objectify bodies (especially women’s bodies); in this regard, we discuss biocapitalism and digital consumption, as well as who controls the narrative around representations and understandings of sex and pleasure.

3D bioprinting process of a clitoris form seeded with cardiomyocytes, in a support gel © WhiteFeather Hunter, 2023.

Menstrual cells in the process of differentiation on the neuronal pathway © WhiteFeather Hunter, 2023.

Ethics of sexuality

The creation of a 3D bioprinted clitoris that is possibly capable of neural processing introduces profound ethical questions around the concept of consent. As previously indicated, consent is understood as a voluntary agreement to engage in a specific sexual activity. However, the parameters of consent become deeply complexified when we consider a bioengineered organ that has the ability to ‘perceive’ and perhaps even ‘feel’ in response to stimuli, in a manner akin to sentient beings.

If a bioprinted organ possesses neural capabilities that mimic awareness or decision-making processes, how does this affect its autonomy? Can such a construct have preferences, make choices, or possess a form of will? And if so, how do we respect and ensure consent in interactions with it?

As earlier described, traditional frameworks of consent apply to human interactions where both parties are capable of understanding and communicating their willingness to participate. How do we adapt our understanding of consent when one party is an only partially human or human-derived, bioengineered tissue form? In medical ethics, when an individual is unable to give consent, a surrogate decision-maker is appointed. Could there be a situation where proxy consent is considered for a bioengineered organ, and if so, who would be qualified to provide it? The tissue donor?

Philosophers have long debated the nature of consciousness and experience. If a bioengineered construct can feel and process information, does it have a form of consciousness? Is it sentient? What ethical theories could guide our interactions with such speculative entities, and how would they inform our understanding of consent?

Is it a sentient being?

Scientists have defined cellular synthetic sentience as, “being able to perceive and respond dynamically to sensory information.” This definition provokes a nuanced examination of the distinctions between sentience and consciousness. Sentience, as described, refers to an entity's ability to have subjective experiences and sensations, whereas consciousness implies a higher level of self-awareness, introspection, and the ability to contemplate one's existence.

In drawing parallels, cellular sentience can be likened to a state of unconsciousness or 'dreaming', wherein there is perception and response to stimuli without full awareness. This comparison naturally leads into discussions around phenomena such as wet dreams, which occur in a state of unconsciousness yet involve physiological responses and sensations.

By conceptualising cellular sentience as a form of unconscious perception, we can explore how cells, while not conscious, might still experience a form of ‘dreaming’. This perspective allows for intriguing debates around the boundaries of sentience and how we interpret and understand the experiences of cellular life.

Digital rendering of a speculative synthetic sentient form © Jiabao Li, 2023.

OnlyFans

To represent an in vitro orgasm, we produced an evocative collaborative performance video that features a 3D printed prototype of the clitoris; our chosen platform for its premiere was OnlyFans. The intent behind selecting a platform predominantly characterised by its adult content and intimate creator-audience interaction is to foster direct dialogue around the nuances of this work. Moving forward, OnlyFans will serve as the digital stage where we chronicle the developmental journey of the lab-grown clitorises. It will not only be a space for sharing the biological progress of this synthetic organ but will also be the canvas for the unfolding narrative that surrounds it. Through visual storytelling and regular updates, we aim to engage our audience in a continuous conversation about the convergence of art, science, and sexuality.

This platform choice represents a deliberate strategy to provoke thought and challenge preconceived notions about the intersection of scientific advancement and sensual expression. It's an invitation to our audience to witness the interplay between creation and sensation, to engage with the ethics of such innovation in an open exchange, and to consider the future implications of biotechnology in our understanding of pleasure and the human experience.

3D printed clitoris prototype in a petri dish © Jiabao Li, 2023.

Is it the same as lab-grown meat? The Biopolitics of Pleasure and Consumption

Ideally, both a lab-grown piece of meat, and a lab-grown clitoris would be ‘eaten’ in certain ways so… what’s the difference?

So-called “lab-grown” meat, or “clean meat” is a would-be technoscientific industrial product of “cellular agriculture” wherein animal cells are grown in vitro into an edible form for human consumption. Marketed (to solicit investor and public buy-in) as ‘ethical,’ ‘revolutionary,’ ‘ecological,’ and even ‘vegan,’ the concept of lab-grown meat is entrenched in moral purity.

Patriarchal attitudes towards women’s sexuality often associate pleasure with immoral behaviour, one of the premises behind cultural practices of female genital mutilation. Since the time of the European witch hunts, the clitoris has been perceived as an embodiment of evil. Possession of a so-called “witch’s teat” (clitoris) was offered as evidence of demonological witchcraft, since Lucifer supposedly suckled from it. More contemporarily, clitoridectomies (surgical removal of the clitoris) have been performed to ‘cure’ masturbation in women; some believe the procedure promotes “cleanliness.”

While our laboratory protocol for culturing 3D bioprinted clitorises is a similar to some of the tissue engineering methods used to cultivate lab-grown meat, it has not been industrially scaled for mass consumption but rather maintained as a small, personalised, synthetic hybrid tissue form designed to investigate notions of (female) erotic pleasure.

“The clitoris is the only known human organ that has the singular purpose of providing pleasure.” Our in vitro clitorises could inspire the design of prosthetic organs for transplant into bodies that have been subject to removal procedures such as female genital mutilation/cutting, but what if they were implanted elsewhere? What if everyone had access to the experience of a clitoral orgasm? Alternatively, could the clitoris itself experience orgasm within the fluid environment of its petri dish? What might an in vitro orgasm look like?

Biocapitalism

Some adult film actors sell “fleshlights” (a kind of sex toy) that are moulded from their vaginas to give their fans a more personalised experience. With a lab-grown clitoris, sex workers could potentially grow multiple clitorises from their menstrual stem cells and commoditize them. What would we be selling if we consider them ‘living’ beings with limited autonomy? Who has the right to capitalise on them as a surrogate orgasm product?

The potential for patenting and profiting from biologically derived materials implicates concerns of biocapitalism. Should biotechnological advancements derived from one's own body be considered personal property, and how do we address the commercialization of such intimate aspects of our biology?

Installation view at Duende Art Museum, China

Talk at Exploratorium: Sexplorations. San Francisco

Jiabao Li, WhiteFeather Hunter, Lera Niemackl

Videographer: Teresa Nichta

Assistant: Melissa Donnelly, Cooper Galvin

Editor: Jiabao Li

This project is generously supported by the Canada Council for the Arts and the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Quebec.